What is shochu?

After sake (nihonshu), shochu is the second traditional drink of Japan.

Shochu is a destillate that was originally produced in Japan, contains about 25% alcohol by volume and was first produced on the island of Kyushu in the south of Japan.

Shochu is normally divided into two categories: the singly distilled premium brands such as Honkaku shochu or Awamori and multiply distilled mass-produced products such as Korui shochu.

Here at shizuku, the expression shochu always refers to the singly distilled premium brands.

Honkaku shochu and Awamori are spirits that are produced in a process called pot still distillation. The majority of this destillate contains about 25 per cent alcohol by volume, some up to 45 per cent alcohol by volume. In Japan, this is the upper limit regulated by law. Honkaku shochu and Awamori are therefore stronger than wine or sake but are mostly weaker than whisky or other spirits known in Europe or the US.

Honkaku shochu has been produced in Japan since the sixteenth century. Machines for distillation were imported to the Ryukyu chain of islands from Indo-china and then sent to Satsuma – the western part of the present-day Kagoshima Prefecture on Kyushu. This is one of the reasons why Kyushu is the home of shochu. Depending on the area, shochu are produced on the island of Kyushu with different regional main ingredients.

Awamori, which was originally produced on the Ryukyu islands (Okinawa), has also been brewed in Japan since the fifteenth century. Only long-grained Thai rice and black koji are used in its production. With 30 to 43 per cent alcohol by volume, it is higher than that of Honkaku shochu.

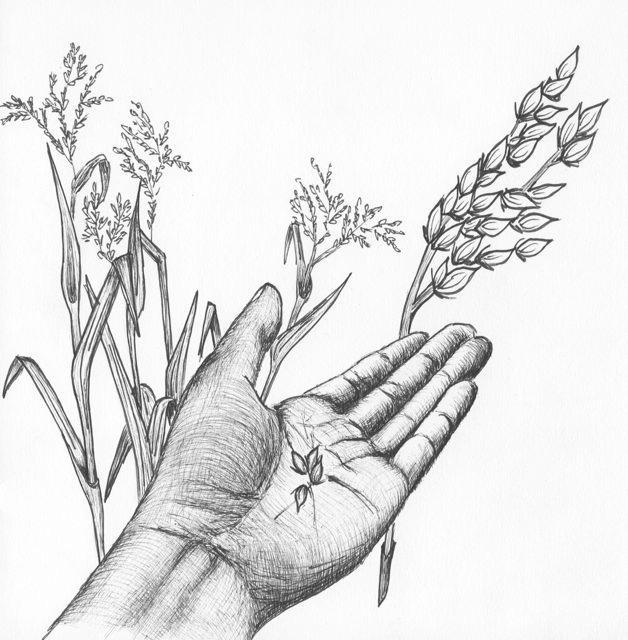

Honkaku shochu is brewed from the following main ingredients: barley, rice, sweet potato, sugar cane, sesame or buckwheat. It is clear from such different ingredients alone how broad the bouquet variety of shochu is.

Shochu is a multifaceted drink, which can be enjoyed in different ways depending on the season and your personal taste (drinking experience). Shochu is also a great accompaniment to meals.

Base ingredients

Base ingredients - barley, sweet potato, rice etc.

Depending on the variety, the main component is added in the production process once the second mash has received the relevant treatment. It is this mash that gives the alcohol the base for its bouquet.

If you want to know more about the main ingredients, you can read more about this subject in the section on shochu varieties.

Water

No alcoholic drink can be produced without water. The same also goes for shochu, which contains up to 70 to 80% water. In Japan, natural water is usually soft and therefore low in minerals - something that is preferential for the production of shochu. Using soft water can bring out a distinct bouquet and also intensify the flavour of the main ingredients.

Koji

Koji are Aspergillus oryzae fungi. In the shochu production process, it is usually rice - less frequently, barley - that is inoculated with koji. This creates enzymes, which break down the starch in the steamed rice and as a result, dextrose, which is essential for the fermentation process, can be produced. In the section on shochu production, shizuku explains which varieties of koji are used to produce shochu and to what extent the choice of koji affects the flavour of the final product.

Production

Washing, soaking and steaming rice

As in the production of sake (nihonshu), koji-rice, which is rice fermented with yeast, is made by first washing the rice, soaking it and then steaming it.

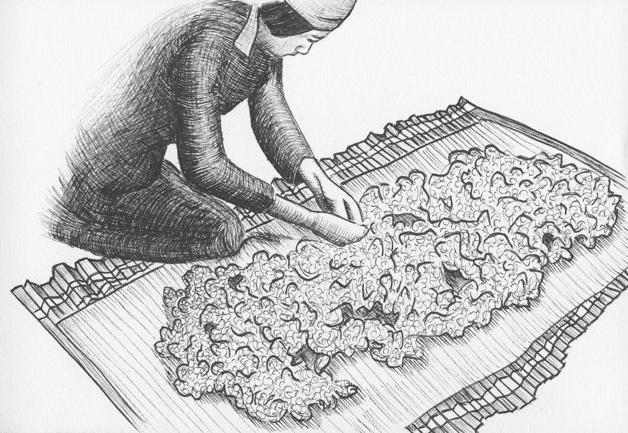

Making rice-koji

The steamed rice is then inoculated with koji (Arpergillus oryzae mould). The enzymes that are created in this process break down the starch in the steamed rice and as a result, dextrose (glucose), which is essential for the fermentation process, can be produced.

It normally takes between 36 and 48 hours to produce rice-koji. It is only at this point that the rice-koji has attained the desired balance of flavour, temperature and bouquet and that the enzyme content and chemical substances are ready for further use. Afterwards, the rice-koji is cooled to prevent the fungus from reproducing any further.

Unlike in production of nihonshu, there are three different types of koji that can be used to create shochu: yellow, white and black.

Yellow koji are also used in the production of sake. As this type of koji mould is very sensitive to changes in temperature, to prevent acidification in the mash (moromi), the temperature has to be carefully monitored during fermentation. In the warm, southern regions of Japan, this poses a significant challenge. Shochu that have been produced with yellow koji are usually strong and fruity and therefore also very popular among the younger generation.

White koji are easy to cultivate and the enzymes allow for quick saccharification. For these reasons, the use of white koji mould has been widespread since the Taisho period (1912 to 1926). The final product has a refreshing, mild and syrupy flavour.

Black koji are most effective in extracting the flavour and character of the base ingredients. Black koji moulds produce a lot of citric acid, which counteracts acidification in the mash (moromi). Thanks to the what is known as the ‘new black koji’ (new kuro koji), a strong, syrupy and mild bouquet of the highest quality is achieved. Since the 1980s, new kuro koji have increased in popularity.

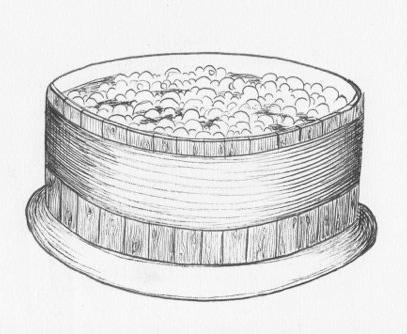

Making the first mash (first stage moromi)

At this point, rice-koji, water and yeast are mixed together in a vat and the first fermentation process begins. During the production of first stage moromi, the temperature has to be monitored carefully. The aim of this step is to encourage the yeast, which is responsible for alcohol production, to multiply.

Rice-koji is normally used in the production of first stage moromi. However, a trend has recently developed in which either 100 per cent barley or 100 per cent sweet potato are used.

A 100 per cent barley shochu is not made with rice-koji, but, as the name suggests, with barley-koji. Nevertheless, the preparation process for barley-koji production is basically the same: hulling, washing, soaking and then steaming the barley grains before they are covered with the koji-moulds.

Preparing the base ingredients

After this, the base ingredients are prepared and then added to the first stage moromi.

First of all, the barley (mugi) is hulled and then polished, as is the case with rice in the production of sake. Similar to the rice polishing ratio (seimaibuai) in sake, in shochu production there is a barley polishing ratio (seibakubuai), which is normally about 60 per cent. The barley grains are polished to remove any unwanted materials such as proteins and fats in the outer layer.

The sweet potatoes (imo) are first washed, sorted, steamed for about an hour and then crushed. So that the potatoes can be used in the production process, they are made smaller to lessen their fibrous consistency.

The rice that is used in the production of kome shochu is called (kome) and is invariably cultivated in Japan. So that the rice can be used in the production process, it is first washed, polished, soaked and then steamed.

In the production of sake rape shochu (kasutori / sake kasu), the residue left over after pressing out the sake is mixed into the main mash in its original form.

Sesame (goma) is added to the fermented rice-koji or barley-koji in its original form. Because of its high fat content, sesame usually only makes up 10 to 20 per cent of the mash. This stops the final product from taking on a fatty and oily flavour. Unlike in most of the varieties listed above, it is not sesame that is added to the main mash (second stage moromi), but the homogeneous liquid that was produced following the primary fermentation before this is distilled.

In the production of Awamori, it is only Thai-rice from the Indica group that is used. The grains are long, thin and the fat and protein content is low in comparison with Japonica rice. The Thai rice is washed, polished, soaked and then steamed.

Brown sugar (kokuto) is first dissolved and then added to the main mash. In comparison with the production of most of the varieties listed above, in brown sugar shochu, the sugar is not added to the main mash in one but in two stages before this is distilled. This two-stage process enables the yeast to remain active and as a result, allows for a trouble-free fermentation process.

Because buckwheat (soba) is not capable of much fermentation, a mixture of soba and rice or soba and barley is normally used in the production of soba shochu. After undergoing heat treatment, the buckwheat is hulled and added to the rice or barley mash in this state.

Making the main mash (second stage moromi)

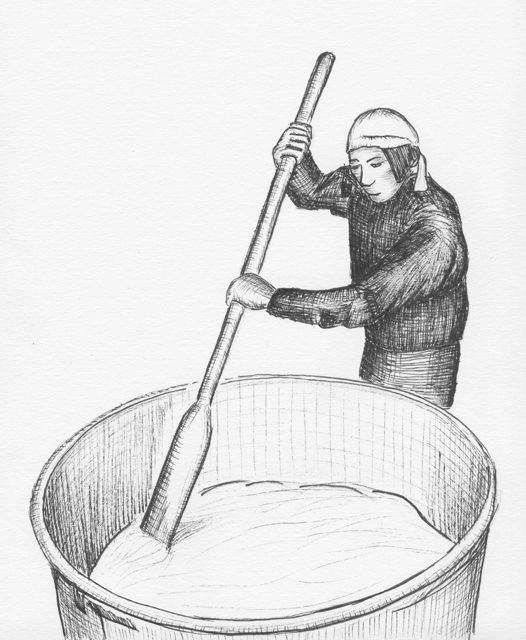

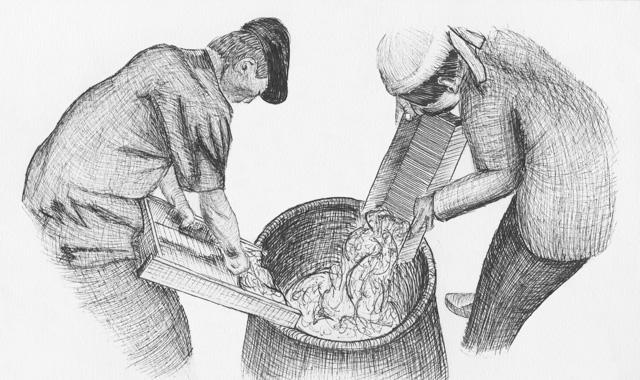

The relevant base ingredient is added to the first stage moromi, which has completely fermented after approximately six days. The mixture is then stirred until it is homogeneous. In traditional distilleries, the master distiller still carries out this process today with a type of paddle.

In the primary fermentation, the koji moulds convert the starch in the respective base ingredients into sugar, which in turn is converted into alcohol. This process lasts approximately eight days. The result is a clean, homogeneous and somewhat viscous liquid.

By virtue of the acidity created by the koji mould, a sour, mild alcohol scent is now diffused, which corresponds more and more to the final product shochu. Up until this point, the main mash, which contains about 14 per cent alcohol by volume, still had to be distilled.

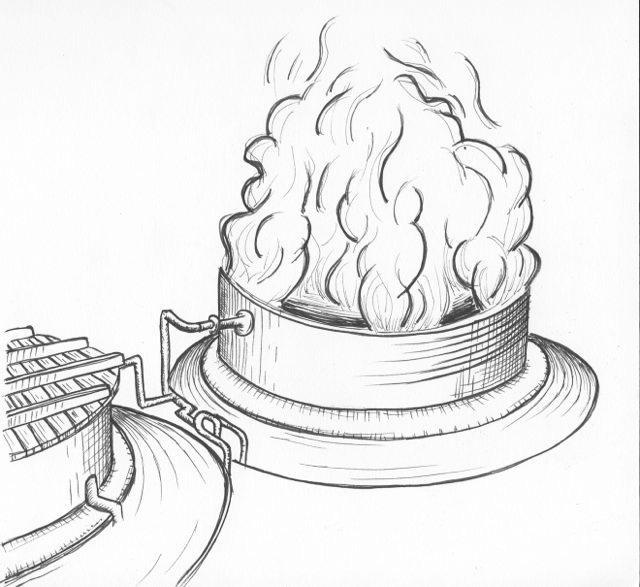

Distillation and storage

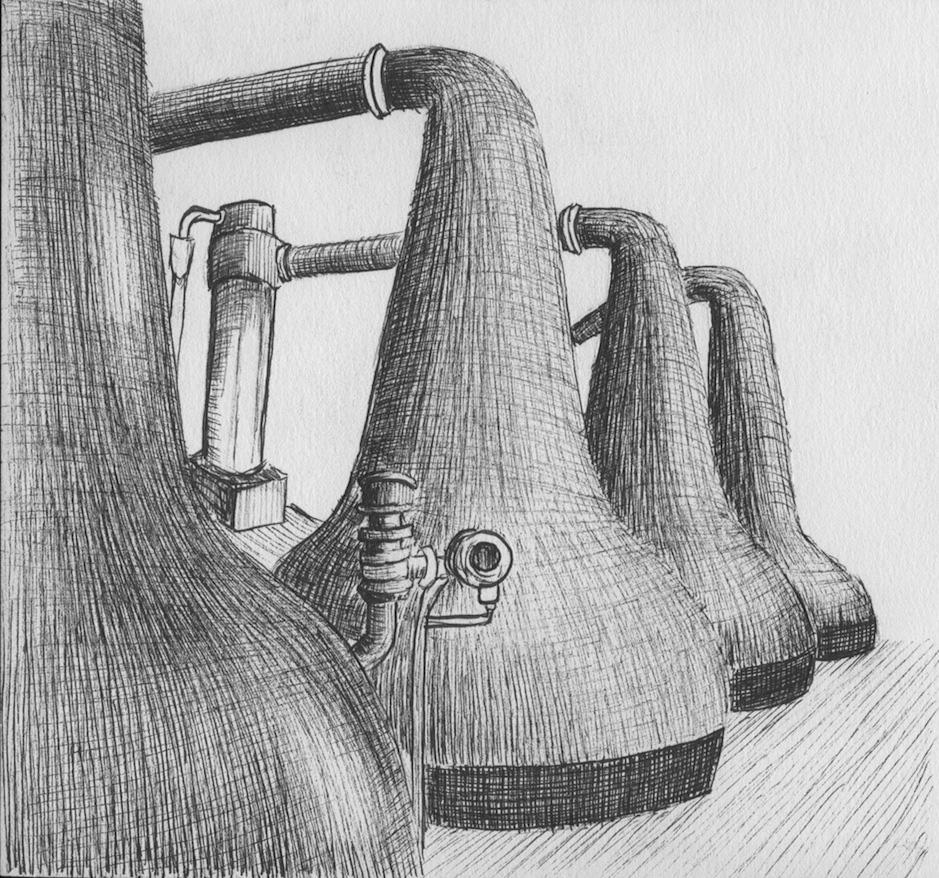

Shochu is produced with the traditional pot-still method. Alcohol distillation is intermittent. This means that only one batch can be distilled at a time, and after each one, the still has to be completely cleaned.

As far as shochu distillation is concerned, there are two methods used:

With low pressure (40 to 60 degrees Celsius), the shochu produced are more refreshing and mild.

With standard pressure (approximately 90 degrees Celsius), the shochu produced are stronger and the flavour of the base ingredient is more intense.

The distilled liquid, which is abstracted through a tap, contains a very high alcohol by volume percentage of about 70 and is called hanatare. Subsequently, it is stored for about three months and as a result, it develops a mild, balanced bouquet.

Bottling

Once it has been stored, a shochu is blended or diluted with water, just as with blends in whiskies. Depending on the variety and the distillery culture, it is at this point that a shochu is bottled or, prior to this, left to mature for another few years.

Normally, shochu contains 20 to 25 per cent alcohol by volume. For shochu, the legal upper limit in Japan is 45 per cent.

Classification

In accordance with the Japanese liquor tax law, shochu is divided into two categories: singly distilled shochu and multiply distilled shochu.

Honkaku shochu and Awamori are made by single distillation and contain up to 45 per cent alcohol by volume. They are distilled in the traditional way in stills (pot-still method). As a result, the original flavour of the main ingredient (barley, rice, sweet potato etc.) is emphasised.

Honkaku shochu and Awamori have been around for over five hundred years, in which time the individual distilleries passed their own traditional production methods down through the generations.

Korui shochu are distilled twice or more (patent still method) and contain a higher alcohol by volume percentage (up to 95 per cent) when they are abstracted. They are distilled in column stills, which distil the feed mixture continuously and quickly. This significantly reduces production costs.

Korui shochu are industrial mass-produced products. Cheap, imported alcohol is obtained in the fermentation of molasses. It is then in distilled to a neat, tasteless alcohol in huge factories before being diluted with water.

Honkaku shochu and Awamori are completely different from Korui shochu. The first reason for this is that the main ingredients used are not of the same quality. In Japan, these ingredients can be potatoes grown in fertile soil, grains such as rice, barley or buckwheat etc. These main ingredients are fermented with the help of koji in order to produce a first mash (moromi), which is then distilled in a pot still. This allows the rich aromas of the base ingredients to influence the flavour of the final product.

Another reason is that the shochu master uses the full extent of his knowledge in all aspects of brewing, fermenting and distilling when producing Honkaku shochu and Awamori so that at the end, a flavoursome, rounded, high-quality product is created. This is not the case in the production of mass-produced products such as Korui shochu.

Honkaku shochu and Awamori are particularly flavoursome alcohols, which are not just popular among the Japanese.

Varieties

There are four large areas of production of shochu. Depending on the area, the name of the shochu also varies:

Imo shochu is produced in Satsuma (Kagoshima), kome shochu in Kuma (Kumamoto), mugi shochu on the island of Iki (Nagasaki) and awamori on the Ryukyu chain of islands (Okinawa).

Shochu gets its base flavour from one of the main ingredients outlined below.

Mugi (barley)

Mugi shochu (barley shochu) is produced throughout Kyushu, which is south of the main island, Honshû. Particularly well known for mugi shochu is the island of Iki in the Nagasaki Prefecture.

To produce mugi shochu, it is best if the barley grains are large, uniform and have a high starch content. As with grains of rice in the production of sake (nihonshu), the barley grains are first polished to remove any unwanted materials such as fats or proteins. Normally about 40 per cent of the grain is polished away before the production process. Equivalent to the rice polishing ratio (seimaibuai), the barley polishing ratio (seibakubuai) is used in relation to barley.

A lot of mugi shochu are produced using koji-rice, as the temperature rises faster than when mugi-koji is used. However, distilleries are also using exclusively mugi-koji more and more in order to produce a 100% mugi shochu with a refreshing gentle and distinct barley flavour.

Imo (sweet potato)

Particularly famous for producing imo shochu (sweet potato shochu) are the Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures in the south of Japan as well as the Izu islands (Tokyo) in the east.

At 25 per cent, the starch content of sweet potatoes is less than that of rice or barley (60 to 70 per cent). Therefore, k?ji must be added so that a fermentation process is initiated in the first place. Imo shochu has a rich, steamed sweet potato bouquet, which is still present when the drink is had with ice or when it is diluted with hot or cold water.

There are over forty varieties of sweet potato that can be used in the production of imo shochu. Only the most important varieties are listed here:

Koganesengan and Joy White sweet potatoes have a high starch content. Characteristics of the final product are the sweetness, strong body and the lingering aftertaste. Joy White sweet potatoes create a fruity, distinct, mild and rounded imo shochu. Because of its high starch content, it is primarily the Koganesengan variety that is used in the production of Imo shochu.

Shochu that are made from Shiroyutaka sweet potatoes are distinct, syrupy and light.

Konahomare sweet potatoes create fresh, syrupy and mild shochu.

Daichinoyume sweet potatoes create fruity Imo shochu with a slight note of citrus.

A strong potato aroma and full-bodied sweetness are characteristics of shochu made of Tokimasari sweet potatoes.

Kome (rice)

The Kumamoto Prefecture in particular, which is located in the south of Japan, is well known for the production of kome shochu.

Nihonshu rice is often used to produce kome shochu and the end product is usually viscid, fruity and has a pleasant, syrupy hint of rice. Because of their mild character, kome shochu are particularly well suited to shochu novices and nihonshu connoisseurs alike.

Sake kasu/kasutori (sake rapes)

Sake kasu are the residues from pressing out sake as part of the production process. A lot of sake kasu shochu or kasutori shochu are produced in sake breweries throughout Japan and in the Fukuoka and Oita Prefectures in the south of Japan in particular. The process requires the sake residue to be distilled in its original state. The sweetness of the residual rice is particularly popular among sake connoisseurs.

Goma (sesame)

So that the large amount of fat-like substances present in sesame do not lend the finished shochu an unwanted fat aroma, approximately 10 to 20 per cent of the sesame is added to the rice or barley used in the production of the first mash. The result is a milder shochu with a pleasant and subtle sesame flavour.

In addition, sesame contains the substance sesamin, which enhances liver function and accelerates the breakdown of alcohol in the blood. Sesame and alcohol therefore assist one another.

Awamori (awamori)

Awamori is produced in Okinawa and is related to shochu. In the production of awamori, it is only Thai rice (Indica group) that is used. These grains of rice are characterised by their length and low fat and protein content. Furthermore, awamori is only made with black koji. This is why black koji is also known as Aspergillus awamori.

The entire mash is only distilled once in one go, thereby strengthening the unique flavour of the awamori. The alcohol by volume of awamori is on average 30 to 43 per cent, and therefore higher than that of shochu.

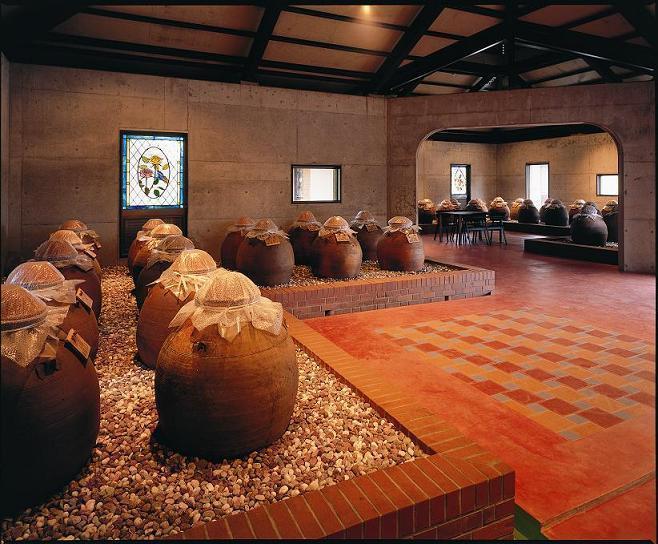

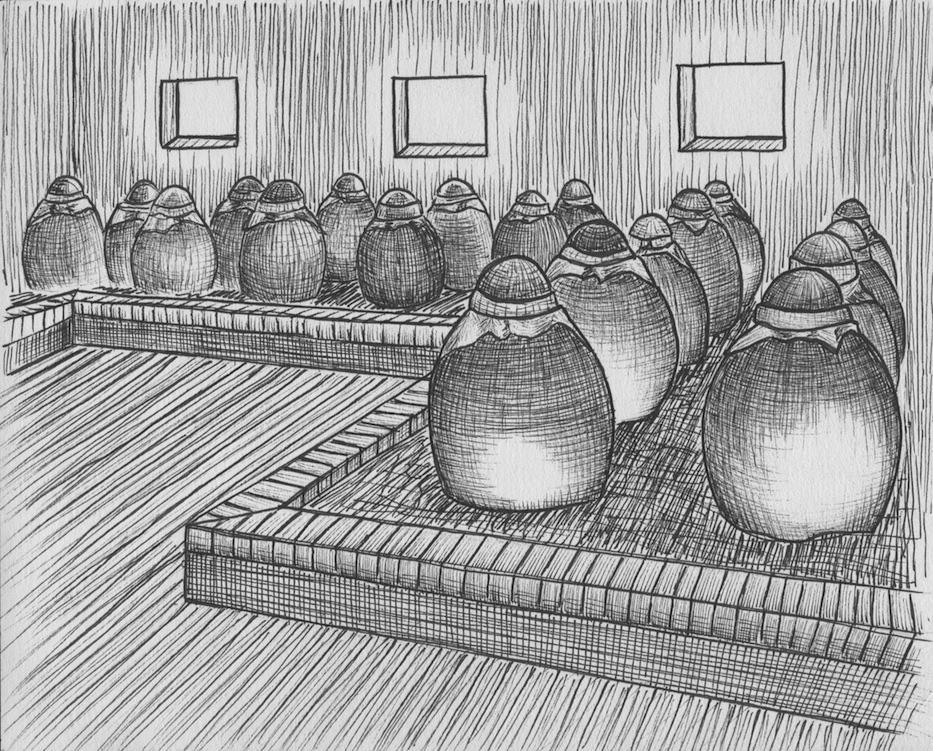

Awamori mature in traditional clay pots (kame) to achieve a mild, balanced taste.

Kokuto (cane sugar)

Kokuto shochu is a regional speciality of the Amami islands. This shochu is produced by distilling cane sugar, which contains a lot of vitamins and minerals. Kokuto shochu are usually sweet and mild.

The production of kokuto shochu is often compared to that of rum. However, the difference is that, in the production of kokuto shochu, a certain amount of cane sugar is added to the second koji-rice mash, a step that is not included in the production of rum.

Soba (buckwheat)

Soba shochu has only been around since the beginning of the 1970s. Famous areas for the production of soba shochu are the Prefectures of Miyazaki (south-west of Kyushu) and Nagano (central Japan).

Before entering the production process, the buckwheat grains that are used have to be hulled with the help of heat treatment. Because buckwheat is not capable of much fermentation, soba shochu are usually made with rice-koji or barley-koji. Soba shochu are fresh and aromatic in flavour.

Drinking experience

There are no set rules that say how shochu should be drunk. Shizuku encourages you to find your own ways of drinking shochu and awamori, according to the season and personal preference.

Traditionally, shochu is drunk from Japanese shochu cups.

The following traditional ways of serving shochu are common in Japan:

Straight

Enjoy shochu neat in any glass you like (shochu cup, choko, wine glass etc). The true flavour of the base ingredient really comes into its own at room temperature. In summer, the bottle can be chilled and the drink enjoyed cold.

On the rocks

First of all, fill a glass or shochu cup with ice and swivel the contents around to cool the glass. Then pour the shochu on top of the ice, give it another slight stir and your drink is ready.

Mizuwari

First, put some ice in a glass or shochu cup. Then pour in the shochu and dilute it with cold water. When diluting with water, the alcohol does not lose any character, bouquet or scent. However, the alcohol by volume is reduced, allowing shochu to also be a very good accompaniment to meals.

Oyuwari

First, pour hot water (approximately 70 °C) into a shochu cup and then pour in the shochu. Because shochu is heavier than water, it mixes naturally and a rich bouquet can be produced. Shizuku recommends a drinking temperature of about 40 °C to strengthen the pleasant taste.

Maewari

Fill an already opened bottle of shochu with water. It is up to you to decide on the ratio of shochu to water. Briefly turn the bottle upside down, and then let the mixture sit in a cool, dark place for a few days to mature. Heat the shochu-water mixture up to approximately 40 °C and enjoy the pleasant, mature taste.

Shochu is not only a great aperitif but also a great after-dinner drink. Depending on the base ingredient and the way shochu is drunk, this alcohol is also an excellent accompaniment to meals.

Shochu can be mixed with mineral water, green tea or fruit juices as desired. You can also add a slice of lemon for a refreshing drinking experience. Shochu are, of course, also an ideal base or ingredient for mixing premium drinks.